A few days ago I was browsing my Gist collection when I came across a pair of old Python codes, Python 2 to be precise. I wrote these lines in 2012 when I was recently introduced to Python by a coworker. So I thought “Why not review them?”, and here we are.

Before we start let me tell that both scripts are about game development, more precisely procedural terrain generation. Let’s take a look at them.

Spiral Flood Link to heading

# Don't work =(

tiles = []

def spiralFlood(tiles, sx, sy, K, m):

x = y = 0

dx = 0

dy = -1

i = 0

while i < m and i < K*K:

if (-K/2 < x <= K/2) and (-K/2 < y <= K/2):

if 0 <= x + sx < 32 and 0 <= y + sy < 32:

# print (x + sx, y + sy)

tiles[x + sx][y + sy] = "#"

i += 1

if x == y or (x < 0 and x == -y) or (x > 0 and x == 1-y):

dx, dy = -dy, dx

x, y = x+dx, y+dy

return tiles

for i in range(32):

r = []

for j in range(32):

r.append(".")

tiles.append(r)

tiles = spiralFlood(tiles,15,15,32,15)

for k in range(32):

print tiles[i]

If I recall correctly, this was a test of an algorithm that creates masses of water, something like lakes, based on an initial point in a 2D grid. Let’s analyze the code:

- There is a typo in the first line, I know. And sure, the code doesn’t work as expected.

- It is poorly modular, has lots of meaningless single letter variables and magic numbers. These things are ok in an experimental code, but they turn the code hard to read and understand.

- The

spiralFloodfunction isn’t snake cased. If you already know Python well you should know about the Python Style Guide, the PEP 8. - The variable

tilesis shadowed inside the function. Shadowing also makes the code harder to read and understand.

Map Generation Link to heading

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

# -- MAPGEN.PY --

import sys

import math

import random

class Map:

# consts

_FOUR_DIRECTIONS = [(1, 0), (-1, 0), (0, 1), (0, -1)]

def __init__(self, width, height):

self._width = width

self._height = height

self._data = [['#' for x in xrange(width)] for y in xrange(height)]

self._visited = []

for y in xrange(self._height):

for x in xrange(self._width):

self._visited.append((x, y))

def flood(self, x, y, cx, cy, max_distance):

self._data[y][x] = '.'

self._visited.remove((x, y))

for t in self._FOUR_DIRECTIONS:

nx, ny = x + t[0], y + t[1]

if self._visited.count((nx, ny)) == 0:

continue

distance = abs(nx - cx) + abs(ny - cy)

if distance > max_distance:

continue

probability = 1 - (distance / max_distance)

if random.random() <= probability:

self.flood(nx, ny, cx, cy, max_distance)

def spawnWater(self, seeds, max_distance):

for i in xrange(seeds):

k = random.randint(0, len(self._visited) - 1)

t = self._visited[k]

x, y = t[0], t[1]

self.flood(x, y, x, y, max_distance * 1.0)

def printMap(self):

for y in xrange(self._height):

for x in xrange(self._width):

sys.stdout.write(self._data[y][x])

sys.stdout.write('\n')

map = Map(80, 32)

map.spawnWater(16, 10)

map.printMap()

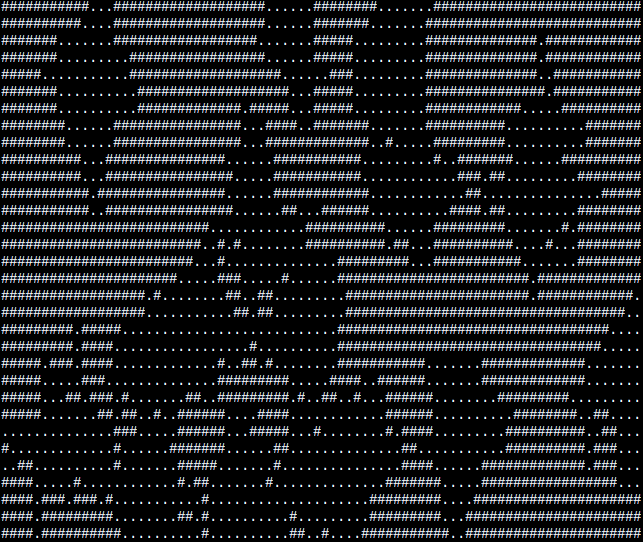

Looks better, right? The objective here is the same as the previous code. It generates a random output every time you run it, something like the following image.

Confusing, I know. Let’s abstract things here: # represents land and . water. Now, taking a close look in the code:

- It is more pythonic, with list comprehensions, tuples, and a class.

- Still not following the PEP 8. You can see I was using a mix of C# and C++ code style. Both languages were my background.

- Every method has a clear job and a good name. This is good.

After all, these scripts don’t look so bad as I imagined. Of course, if I was writing this code today I would change a couple of things like writing the code with Python 3 and using a better code styling. And that’s exactly what we get out of when we review old code: a chance to look back and see what we’ve learned and how we evolved as a developer. And that is all for today. See you next time.